Chapter 1 – Wider Benefits of Transit

- No related sections.

Economic

- No related sections.

Transit helps households save money.

Transportation-related expenses are typically the second largest share of household costs after housing. Nationally, between 2000 and 2012, combined housing and transportation costs increased 44% during the same period that income only grew 25%.[1]

Transit provides an affordable transportation option for those who cannot purchase a vehicle. The cost of vehicle ownership and operation continues to grow, reaching more than $10,000 per year for a medium sized sedan in 2013.[2] The average American household has 2.28 vehicles; 35 percent of households have three or more vehicles. Households encounter a number of costs associated with vehicles, including insurance, licensing, registration, and vehicle taxes. Beyond the sunk costs of purchasing and maintaining the vehicle, the cost of gas, parking, and tolls add additional daily costs. In urban areas, off-street parking requires expensive permits or subscriptions to parking garages. In rural areas, long distances between destinations increase spending on gas and maintenance. The availability of public transportation can help reduce household transportation costs.

Health

- No related sections.

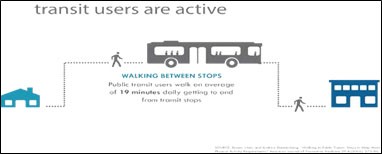

Transit increases physical activity.

Transit increases physical activity. The number of hours of physical activity per week declined 32% among Americans between 1965 and 2009. By 2030, this figure is projected to be 46% below physical activity levels in 1965.[3] Nearly half of Americans do not meet recommended levels of physical activity for adults (30 minutes or more of physical activity per day).[4] The amount of time some spend traveling in automobiles is one contributor to this trend. Taking transit can help increase physical activity and improve health. On average, transit riders walk 19 minutes a day get to and from transit stops.[5]

Transit can help lower rates of obesity and chronic disease.

Inactivity is associated with diseases such as diabetes (Type II), coronary heart disease, hypertension, and obesity. Studies show over 5 million premature deaths per year result from disease related to inactivity[6] and an estimated $2,741 more is spent per year on higher healthcare costs for persons that lead inactive lifestyles.[7] These same individuals are also more likely to take an additional week of sick days per year and live five years less than more active individuals.[8,9]

Promoting the use of transit can help lower the risk of sedentary-related illnesses. The benefits of living an active lifestyle have been shown to cause a:

- 50% reduction in coronary heart disease

- 50% reduction in adult diabetes risk

- 50% reduction in the risk of becoming obese

- 30% reduction in the risk of developing hypertension[10]

Air Quality

- No related sections.

Transit reduces congestion and emissions.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency, transportation is the second largest contributor to GHG emissions, at 26%, after electricity, at 30%.[11] Congested travel contributes to higher levels of emissions from vehicle idling and speed variance. The environment and public health suffer from auto-related emissions, particularly in areas where heavy traffic congregates. Convenient and efficient transit service can help relieve traffic congestion and reduce emissions.

People who live in more rural areas of Greater Minnesota may not experience traffic congestion but must travel long distances for work, healthcare, or other services. If these trips could be combined with public transit service, they could reduce single occupancy travel as well as the associated emissions.

Transit can help curb the effects of climate change.

Climate change will have impacts on the national economy. On our current trajectory, the nation will lose between $66 to $106 billion worth of coastal property by 2050.[12] Extreme heat has significant economic implications for labor productivity and human health. Studies suggest that the frequency of days over 95 degrees will dramatically increase and extreme weather days may surpass the threshold at which humans can work outside, or inside without air conditioning, while maintaining a normal core temperature.[13] This could lead to productivity slowdowns and enormous strain on the energy grid when demand for air conditioning grows. Agriculture crops will also suffer in many areas of the country, including areas that are large agricultural producers. Efficient public transit can help curb effects of climate change by reducing the number of vehicle miles traveled and associated emissions.

Quality of Life

- No related sections.

Transit accommodates an aging population of Baby Boomers.

Baby Boomers are reaching retirement. Between 2000 and 2014, older adults (ages 65 and older) have increased 16% in Greater Minnesota.[14] Between 2014 and 2045, the older adult population is expected to increase by 88%.[15] This large population of older adults will require safe and affordable transit options to stay active and engaged in their communities and access daily services and medical appointments.

Transit allows for aging in place.

The national discussion surrounding the repercussions of the aging population and housing needs is a pressing one in Greater Minnesota, especially given the projected increased in the older adult population discussed earlier. Surveys and research have shown that people want to stay in their homes as long as possible; however, health and other factors sometimes require people to move into assisted living quarters. While research thus far is not conclusive, initial studies by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development authority point out that people who can age in place have better overall physical and mental health.[16]

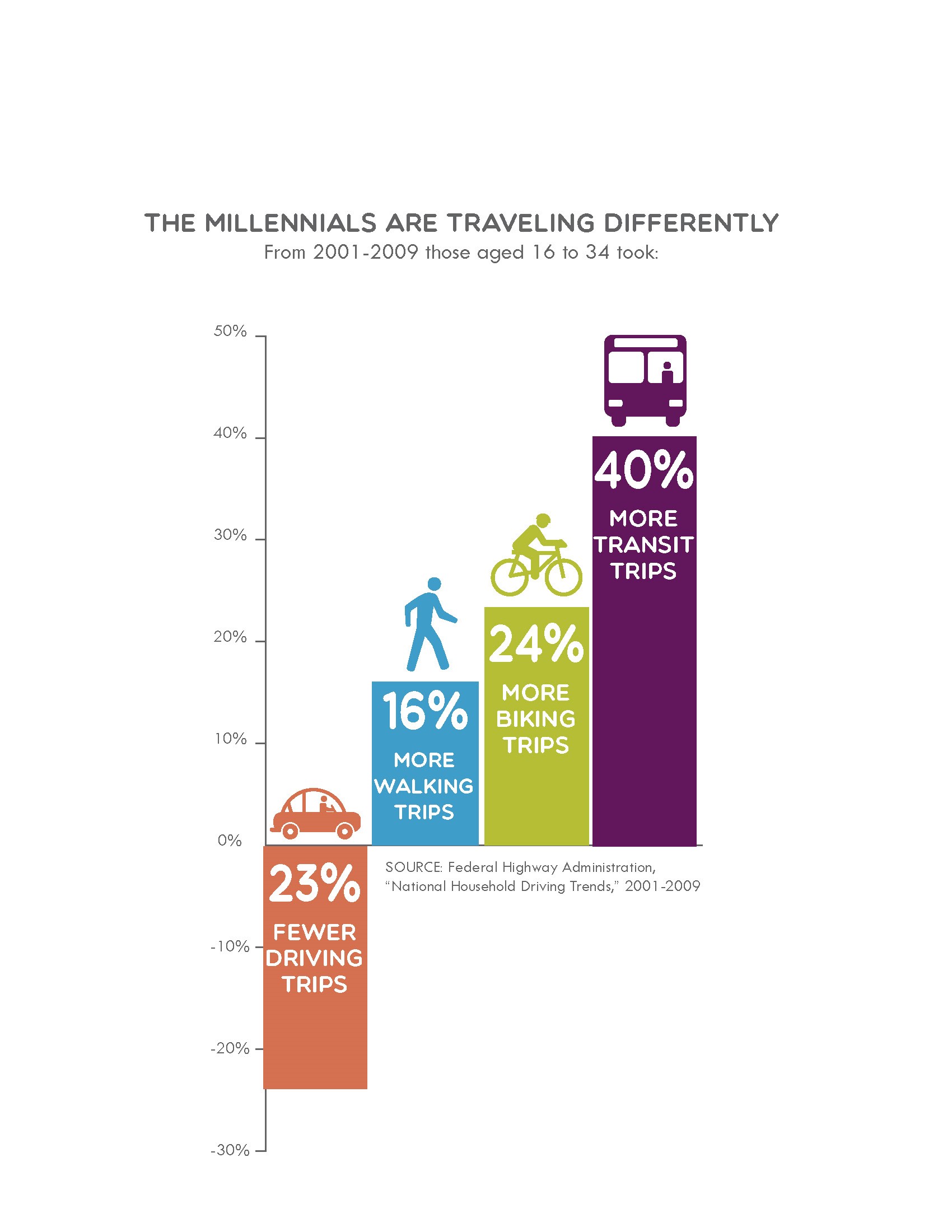

Transit supports changing transportation preferences.

Transportation preferences are changing for a new generation of Americans. The Millennial generation (approximately those born between 1981 and 1997) is driving less and using transit, biking, and walking more.[17,18] Millennials are attracted to communities that offer multiple transportation options. Millennials—and other generations—value transit because it allows them the luxury of working while in transit, staying connected with peers, relaxing, or exercising.

Connections

- No related sections.

Transit can help provide convenient access to community destinations.

The American Community Survey estimates that 9% or 10.5 million households do not have access to a vehicle.[19] Transit provides zero vehicle households an opportunity to connect to education, cultural, social, and recreational outlets throughout their community. These activities help create strong neighborhood centers that are more economically stable, safe and productive. More than 7,200 organization in the U.S. help communities make these connections by providing public transportation.[20]

1. Center for Housing Policy and Center for Neighborhood Technology. "Losing Ground: The Struggle of Moderate-Income Households to Afford the Rising Costs of Housing and Transportation." October 2012. Retrieved from http://www.nhc.org/media/files/LosingGround_10_201...

2. American Automobile Association. "Your Driving Costs." 2013. Retrieved from https://exchange.aaa.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/0...

3. Designed to Move: a Physical Activity Action Agenda, 2012. https://www.designedtomove.org/en_US/?locale=en_US

4. Besser, Lilah, and Andrew Dannenberg. "Walking to Public Transit: Steps to Help Meet Physical Activity Requirements." American Journal of Preventive Medicine 29:4 (2005): 273-80. Accessed at http://www.cdc.gov/healthyplaces/articles/besser_d...

5. Besser, Lilah, and Andrew Dannenberg. "Walking to Public Transit: Steps to Help Meet Physical Activity Requirements." American Journal of Preventive Medicine 29:4 (2005): 273-80. Accessed at http://www.cdc.gov/healthyplaces/articles/besser_d...

6. Lee, I., et al. "Effect of Physical Inactivity on Major Non-Communicable Diseases Worldwide: an Analysis of Burden of Disease and Life Expectancy. The Lancet 380.9838(July 2012): 219-29.

7. Cawley, J. and C. Meyerhoefer. "The Medical Care Costs of Obesity: an Instrumental Variables Approach. Journal of Health Economics 31.1 (January 2012): 219–30.

8. Proper, K.I., et al. "Dose-response Relation between Physical Activity and Sick Leave." British Journal of Sports Medicine 40.2(2006): 17-78.

9. Olshansky, S.J., et al. "A Potential Decline in Life Expectancy in the United States in the 21st Century." New England Journal of Medicine 352.11 (2005): 1138-45.

10. Litman, 2009.

11. EPA. Sources of Greenhouse Gas Emissions. 2014. Retrieved from https://www3.epa.gov/climatechange/ghgemissions/sources/transportation.html

12. Houser, T., et al. "American Climate Prospectus: Economic Risks in the United States." The Rhodium Group. June 24, 2014. http://rhg.com/reports/climate-prospectus

13. Houser, T., et al. "American Climate Prospectus: Economic Risks in the United States." The Rhodium Group. June 24, 2014. http://rhg.com/reports/climate-prospectus

14. US Census and American Community Survey 2014.

15. American Community Survey 2014 and Minnesota State Demographic Center.

16. US Department of Housing and Urban Development. Retrieved from https://www.huduser.gov/portal/periodicals/em/fall...

17. Pew Research Center. April 2016. Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/04/25/mi...

18. US PIRG. Millennials in Motion. October 2014. Retrieved from http://www.uspirg.org/reports/usp/millennials-moti...

19. American Community Survey, 2014.

20. American Public Transportation Association. Retrieved from http://www.apta.com/mediacenter/ptbenefits/Pages/F...